At the annual general meetings of the Intergovernmental Forum on Mining, Minerals, Metals and Sustainable Development (IGF) earlier this month, the main theme was the role of mining in a world where climate concerns are front and center. But as the world changes in multiple respects, from the increased use of renewables to the digitalization of work, taxing the activities of mining companies has only become more challenging.

Mining is a critical element in policy strategies aiming to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The sector contributes an estimated 1.25 to 11 percent of global emissions (depending on definitions used). Efforts by companies and the governments of major mining jurisdictions to increase the share of renewable energy used in the mining sector are therefore welcome. Better measurement of environmental and social impact would also help, as would improved guidance on the subject from the IGF. Meanwhile, the latest renewable energy technologies, especially in solar, wind and batteries, require increasing amounts of minerals such as cobalt, lithium and graphite (which had fewer uses in the past) and new supplies of more established commodities such as bauxite and copper.

These trends are gathering pace as the digitalization of the economy has affected tax collection and spurred a global debate on the taxation of multinational companies, with recent proposals from the OECD/G20 Inclusive Framework going much further than the initial scope of the OECD’s 2013 base erosion and profit shifting action plan. But these proposals are led by the world’s major powers, and they will likely just move consumer-based multinational companies’ taxable profits from low-tax jurisdictions to large markets, mostly in the G20.

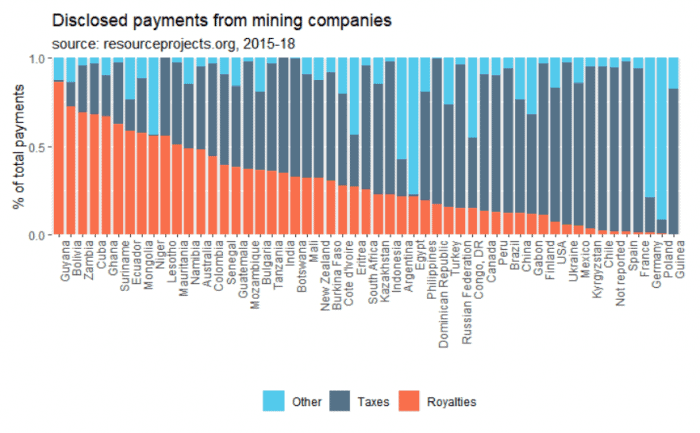

In the meantime, developing countries face enduring challenges in taxing mining companies. Most countries’ fiscal regimes for mining include a mix of production-based taxes, typically royalties or export taxes, and profit-based taxes. To create the figure below, we pulled data on payments to governments from resourceprojects.org, disclosed by mining companies listed in the European Union or Canada over the last three years, showing what proportion of these payments were royalties, taxes (mostly corporate income taxes), or other types of payments. Although the data do not represent all revenue from mining in these jurisdictions, they do show a wide range of tax collection realities. For some countries on the left side of the figure, royalties represent more than half of all payments declared by mining companies, reflecting governments’ difficulties in collecting income tax, which are typically easier for corporate taxpayers to avoid. Both tax and royalties depend on a proper assessment of production quantity, quality and value, but income taxes can also be minimized through the mispricing of costs.

When governments struggle to collect profit-based taxes, they might be tempted to rely more heavily on royalties or other production-based taxes, as recent examples in the DRC, Indonesia and Zambia illustrate. But fixed ad valorem royalties lack flexibility: they do not adjust well to the profile of mining investments, nor to booms and busts. They may cause interruptions in mining activity, or require frequent regulatory changes.

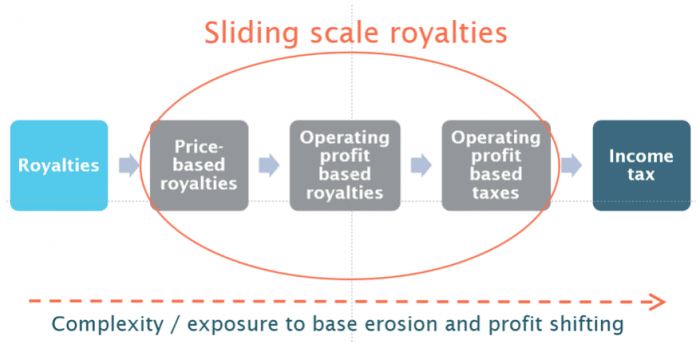

However, the mining sector is rich in alternative tax instruments that provide some middle ground between the reliability and simplicity of royalties, and the flexibility of income taxes. Their rates are progressive, and their bases are somewhat less susceptible to erosion through cost inflation, transfer mispricing and thin capitalization. We classify them in three categories, from the simpler to the more flexible, as illustrated in the figure below:

- Price-based royalties, which are production-based royalties with rates varying according to mineral prices. Examples: Côte d’Ivoire, Bolivia.

- Operating profit ratio based royalties, which are production-based royalties with rates varying according to the ratio of operating profit to gross revenue. Examples: South Africa, Niger.

- Operating profit taxes, which are based on various definitions of operating profits and with rates varying according to the ratio of operating profit to gross revenue. Examples: Chile, Peru.

Because these tax instruments all have rates that slide along a scale, we label them “sliding scale royalties.” In a forthcoming report, the first study dedicated to these types of taxes, we will explore the design of these different categories of sliding scale royalties, review 20 case studies and examine how they fare against the complex evolution of mineral prices and mining costs. The report will suggest a robust way to evaluate and design sliding scale royalties, allowing government officials who worry about both attracting investment and tax abuses to understand when and how to levy them.

Because these tax instruments all have rates that slide along a scale, we label them “sliding scale royalties.” In a forthcoming report, the first study dedicated to these types of taxes, we will explore the design of these different categories of sliding scale royalties, review 20 case studies and examine how they fare against the complex evolution of mineral prices and mining costs. The report will suggest a robust way to evaluate and design sliding scale royalties, allowing government officials who worry about both attracting investment and tax abuses to understand when and how to levy them.

David Manley and Thomas Lassourd are senior economic analysts at NRGI. Tommy Morrison contributed data analysis and visualization to this blog post. Anna Fleming is a co-author on NRGI’s upcoming report on sliding scale royalties, from which analysis was drawn for this piece.