Governments have been working to increase the amount of goods and services purchased by mining companies operating within their borders over the last decade, in addition to long-standing efforts to ensure more employees are domestic nationals.

At the same time, automation and other technological advances have begun to pose a threat to this local content agenda. As shown in the IISD report Mining a Mirage?, automation can lead to reduced employment and less procurement. Fewer employees mean fewer camp services, uniforms, and other products, which are often supplied by national suppliers. Technological advances make mining processes more efficient, but this also means demands for maintenance services are lowered.

Then came 2020. The COVID-19 pandemic has caused a fundamental rethinking of operations in mining—and across every sector, for that matter.

On the one hand, the COVID-19 pandemic has made governments and companies in all countries and sectors think more about their supply chains for the first time. Shortages of personal protective equipment (PPE) in hospitals dramatically showed how entirely relying on imported goods can lead to disaster.

Many mine sites were cut off from expatriate employees and international service providers who could not travel to the site, and many also faced shipping disruptions for goods.

In this regard, mining companies now clearly have a common purpose with governments who want to create domestic supplying firms. It is undoubtedly in governments’ economic interest to have access to more competitive suppliers of goods and services, as well as more local employees for critical roles.

On the other side, pressures on mining companies to automate will grow even further, as having a workforce that does not require travel to a site will be a way for mining companies to help ensure activity can continue in the event of future travel restrictions.

There are thus potential pitfalls and opportunities that host country governments face in trying to increase local hiring and procurement of goods and services amidst these challenges.

Fortunately, the answer to both of these challenges begins with the same thing: data.

The only way governments can adjust their strategies to increase local content is to have more detailed information on the current state of mining sector procurement and on employees.

This kind of data includes:

- What percentage of goods and services currently being produced in-country for mining operations will be displaced by automation and other new technologies?

- What types of goods and services are subject to disrupted supply from international suppliers in the event of pandemic-like events, and in what volume?

- What sophisticated mining jobs are currently being carried out by expatriates?

Only with these kinds of breakdowns from companies can governments create the appropriate strategies in terms of local content policies, investments in education, and infrastructure provision.

There are positive signs that many mining host countries are increasingly understanding the value of collecting detailed information from mining companies on what they are procuring and how they are seeking to increase local procurement.

Ghana, for example, has had regulations in place since 2012 that require mining companies to procure a list of goods and services locally or else face fines. Currently, there are 28 goods and services listed. Companies must create a 5-year local procurement plan and report their spending on these particular listed products each year. This targeted approach allows the Ghanaian government to track progress on national efforts to build up suppliers of those listed goods. This level of detail allows them to monitor and adjust policy in a much better way than if they did not have data broken down by products.

In addition, many countries in the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) are beginning to collect more information on local procurement and other aspects of local content in general. As of March 2018, 24 EITI countries were already including some information on local content in their reporting, and, in late 2019, the EITI board agreed to explore sharing more best practices for transparency in procurement processes.

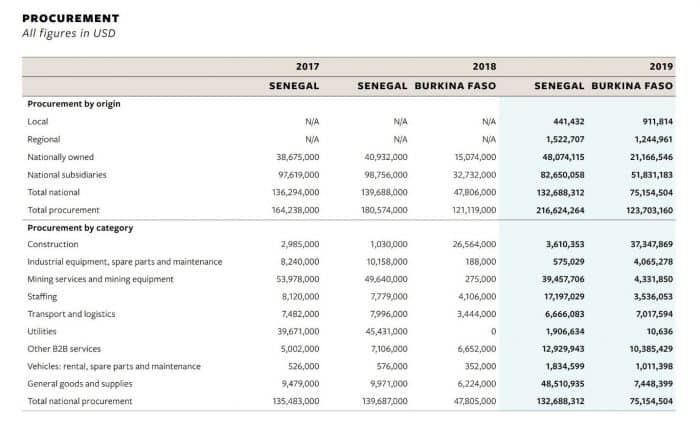

A particularly exciting example of leadership in this regard is EITI Senegal, which now collects and publishes statistics on what percentage of procurement by mining (and oil and gas) companies goes to national versus international suppliers.

For our part, working with the Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ), we created the Mining Local Procurement Reporting Mechanism (LPRM), which is a publicly available reporting framework that guides mining companies to provide detailed and standardized information. It encourages companies to break down their procurement into increasingly more sophisticated categories of types of suppliers (e.g., local, national, women-owned) and into more categories of goods and services.

Figure 1. Teranga Gold, who uses the LPRM, provides a detailed breakdown of how much spending goes to different types of suppliers for broad categories of goods and services

The key point is that governments require detailed data from mining companies on what they are buying, their procurement processes, and the precise makeup of their employees in order to develop effective policies for local content.

With the impacts of COVID-19 and increasing automation, detailed data is even more important for governments to understand mining sector requirements.

The preceding is a guest blog and does not represent the views or opinions of the IGF Secretariat or its member countries.