Those of us involved in the mining sector could be forgiven for thinking that the OECD’s program of work on digital tax reform does not apply to us. Companies such as Facebook and Amazon seem to be the obvious targets—i.e., highly digitalized businesses that operate remotely from the countries where their sales arise and thus avoid having a taxable presence.

Mining, on the other hand, remains a “bricks and mortar” business (although take-up of digital technologies is increasing). The physical presence of a mine, not to mention public ownership of the resource, creates an irrefutable obligation to pay tax in the resource-owning country.

However, the OECD program to tax the digital economy, which has become somewhat of a misnomer, will apply to all businesses that are within its parameters, making it critical to fashion this intended scope clearly or to include a carve-out for certain sectors.

Under the so-called “Unified Approach,” a new taxing right will be established in the market or destination country (i.e., where the goods end up). This first part is called “Amount A,” and it means that a company that is not physically present in the country where its consumers are located will have a tax “nexus” based on its sales. In the case of mining, this would mean some of the profits from the sale of minerals would be transferred from the resource-owning country, and residence country, to the customer’s location.

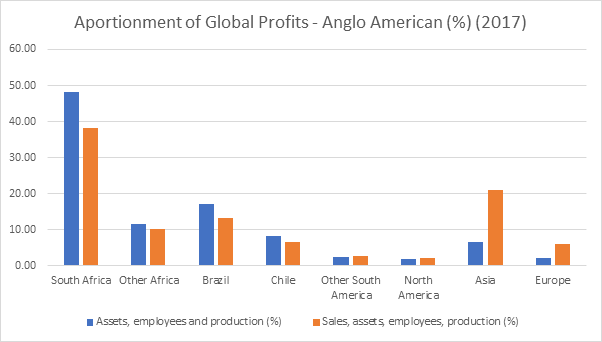

Taking Anglo American as an example, if sales were added as a basis for allocating profit (see orange bar below), the share of global profit would fall in the resource-owning countries (e.g., South Africa, Brazil, Chile) and increase in the market countries (e.g., Asia [primarily China] and Europe).

Source: Calculations are based on Anglo’s 2017 Financial Statement. Data used is illustrative.

It is up to the 135 countries that make up the Inclusive Framework to decide whether mining is within the scope of the new taxing right. The OECD Secretariat’s position so far is that it should not be included. IGF firmly supports the Secretariat’s view for the following reasons:

- Mineral resources are location-specific. Unlike the profits generated for Facebook by Facebook users globally, the profits from mining are tied to a mine, which is a physical operation that is fixed to a specific location. Moreover, the resource is publicly owned, a concept enshrined in many constitutions, making it inappropriate to shift taxing rights away from the resource-owning country.

- Mining is neither highly digitalized nor consumer facing. Even if future mines are operated entirely remotely, the business would still be underpinned by a location-specific, immovable resource.

- There is limited value generated from marketing intangibles (i.e., branding). The price that minerals and metals are sold for is generally underpinned by market prices that reflect the physical characteristics of the commodity (e.g. % of copper contained).

Possible minimal linkages to consumers should not alter this. De Beers, for example, sells diamonds directly to consumers in the United States and China. However, this segment of the value chain contributes very little to De Beer’s total profits,[1] which remain tied to diamond mines in Botswana and Southern Africa. Singling out this part of the value chain risks transferring taxing rights away from resource-owning countries. For these reasons, plus ease of administration, the whole mining value chain should be out of the proposed scope.

The second part of the Unified Approach (“Amount B”), ascribes a fixed return on sales to the marketing and distribution activities in the market country. The aim is to avoid disputes with taxpayers over how much profit the market country should get.

Assuming that in the case of mining there is no new taxing right in the market country, a minimum return cannot be assigned (i.e., Amount B does not apply). If, however, Amount B can apply in the absence of the new taxing right, a fixed return on sales would be an inappropriate basis on which to reward marketing activities in the mining sector, because of the lack of marketing intangibles. Following disputes with BHP and Rio Tinto, Australia has ruled that a return on operating costs is a more reasonable basis for remuneration than the return on sales which both companies had been using.

The taxation of mining profits is not without problems. There are many avenues for companies to avoid tax and significant challenges to overcoming these. This is why IGF has a multi-million-dollar program aimed at helping its members safeguard their mining tax base against tax base erosion and profit shifting.

If applied, the Unified Approach will augment rather than reduce these problems for resource-owning countries. A separate process to review the global mining tax system is required. IGF is committed to working with partners – the OECD, ATAF, and CIAT – to design the mining fiscal regime of the future.

IGF’s submission to the OECD on the Unified Approach can be found here, along with that of our partners, the African Tax Administration Forum (ATAF).

[1] De Beers generated revenue of only USD 0.2 billion in 2018 from “Other Diamond Sales” (which is how it classifies its sales of polished diamonds) compared to De Beers’ total revenue of USD 6.2 billion (mostly from the sale of rough diamonds). See https://www.debeersgroup.com/reports/insights/the-diamond-insight-report-2019